On February 24, 2023, the federal Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) announced proposed rules for permanent telemedicine flexibilities surrounding the prescription of controlled substances. According to the DEA’s press release, the proposed rulemaking will extend many flexibilities adopted during the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency (PHE). According to DEA Administrator Anne Milgram, “[t]he permanent expansion of telemedicine flexibilities would continue greater access to care for patients across the country, while ensuring the safety of patients. DEA is committed to the expansion of telemedicine with guardrails that prevent the online overprescribing of controlled medications that can cause harm.” While the proposed rules are certainly more restrictive than the complete waiver of the in-person medical evaluation requirement prior to controlled substance prescribing during the PHE, many telehealth providers will be relieved that the proposed permanent flexibilities are not limited to controlled substances to treat opioid use disorder or other substance use disorder treatment, as many feared would be the case. The proposed rules undoubtedly require some clarification, and the DEA has provided a 30-day comment period to hear from the public. Below are some highlights of the proposed rule[1] and background.

The Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act

The Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008 (The Ryan Haight Act) was intended to protect the public from unlawful distribution of controlled substances through the internet. It was named for a California teenager who died as a result of controlled substances acquired from an online pharmacy that did not require patients to obtain in-person medical evaluations from prescribers. The general rule under the Ryan Haight Act is that a practitioner is required to have conducted at least one in-person medical evaluation of the patient prior to issuing a prescription for a controlled substance. There are seven exceptions to the in-person requirement, where certain methods of telemedicine may be conducted; however, the exceptions do not easily align with direct-to-patient service models frequently sought by patients in areas such as telepsychiatry (e.g., where the patient is at his or her home at the time of the telemedicine consult). Despite the passage of time (14 years) and 2018 Congressional direction to the DEA to take action via the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act (SUPPORT Act), the primary exception designed to accommodate legitimate telehealth models—a special registration—was never implemented. The proposed rules still do not implement such special registration. Rather, in footnote 20 of the preamble to the proposed rulemaking, DEA states that the proposed rules are “… consistent with, and fulfills, DEA’s obligations under the Ryan Haight Act and the Support Act.”

Highlights of DEA Rule

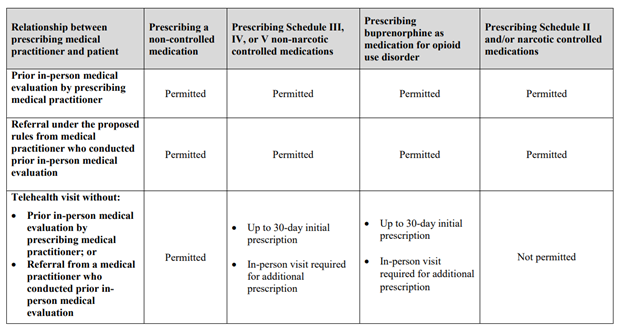

The DEA provided several resources through its press release on February 24 including a Highlights for Medical Practitioners document which provides a good overview of the rules. Additionally, a very high overview was provided by DEA in the following chart:

As depicted in the DEA chart above, the DEA has proposed the permissibility of prescribing controlled substances via telehealth so long as there is a prior in-person medical evaluation by either the prescribing practitioner or a medical practitioner who conducts an in-person medical evaluation and provides a referral to the remote practitioner prior to prescribing controlled substances via telehealth. For many telehealth providers that have been preparing to operationalize for the return of Ryan Haight Act as it stood pre-PHE, this is a welcome flexibility. Specialty telehealth providers, for example psychiatrists, may work with professionals in the patients’ community, such as primary care providers, to coordinate referrals of patients, as appropriate. Of course, for patients in remote or underserved areas, patients with housing insecurity, homebound patients, and others that cannot physically access a practitioner, the in-person medical evaluation requirement, in any form, may be a barrier to care.

Under the proposed rules, practitioners may prescribe Schedule III, IV, or V non-narcotic controlled substances for an initial period of 30 days without any in-person medical evaluation requirement. For additional prescriptions (for any schedule II-V controlled substance) to be issued, the patient would need an in-person evaluation by either: (i) the prescriber, (ii) another practitioner that refers the patient, or (iii) another practitioner that evaluates the patient while the prescriber simultaneously participates in the visit via telemedicine.

In the DEA’s request for comments, the DEA specifically requested comments on “…whether the rules should limit the issuance of prescriptions for controlled medications to the FDA-approved indications contained in the FDA-approved labeling for those medications.”[2] This comment is concerning for providers that may prescribe controlled substances “off-label” including psychedelic behavioral health treatments and certain hormone therapy for gender transition treatment. As currently proposed, the regulations do not restrict telehealth prescriptions to “on-label” uses.

The proposed rules include various, detailed record-keeping requirements including records related to a practitioner that conducts an in-person medical evaluation and then refers the patient for a telehealth visit/prescription, records related to the telehealth prescription itself, and records that must be maintained by the practitioner that prescribes via telehealth. Some clarification is likely necessary on these requirements and the DEA appears to have recognized so in its invitation on comments on the proposed recordkeeping obligations.[3] One potentially concerning requirement is that if one of these new telemedicine options are relied upon, the prescriber must note that the prescription was issued based on a telemedicine encounter on the face of the electronic prescription.[4] Such notations will be new to pharmacies and it is possible that some pharmacies will refuse to fill those prescriptions (given that pharmacies during the PHE at times rejected prescriptions that they determined to be generated from telehealth encounters).

The DEA also proposed that all records that are connected to telemedicine prescriptions and qualifying telemedicine referrals be held at the location on the relevant practitioner’s DEA registration. If such individual holds more than one DEA registration (which new proposed requirement for multiple registrations is discussed further below), then such individual will designate one location to maintain all such records.[5] It is unclear at this time how a provider would “designate” their one location, but DEA’s goal is to ensure it can easily investigate (e.g., for diversion issues) at one centralized location of a DEA registrant rather than in each state the practitioner may have prescribed to a patient or conducted an in-person medical evaluation resulting in a telemedicine referral.

During the PHE, the DEA did not require DEA-registered practitioners to be registered in each state they were prescribing controlled substances to patients. Nonetheless, to prescribe through telemedicine as defined under the proposed rules, the prescriber would need to have DEA registration under the state where the prescriber is located and the state where the patient is located. The proposed rules are silent on how this registration process will work for prescribers who, during the PHE, were only registered in the state where they were located.

An area that has likely caused mixed reactions for telehealth providers is the proposed 180-day “grandfathering” for patients with established telemedicine relationships during the PHE. The PHE is due to expire on May 11, 2023. Many telehealth providers have already been working on potential plans to operationalize models that incorporate in-person medical evaluations that may have been required in forthcoming DEA regulations; however, there was a reasonable expectation that some sort of transitionary period or “grandfathering” of PHE practices would be permitted as the industry adjusts to DEA regulations, when finalized. The proposed DEA rules permit practitioners to prescribe all schedule II-V controlled substances via telemedicine to patients that were prescribed controlled substances during the PHE for a period of 180 days after the rule is finalized.[6] This means that patients that are new to a practitioner the day after the DEA rule is finalized and do not fit one of the pre-PHE Ryan Haight Act exceptions (for example, the patient is not located in a hospital or in the presence of a DEA-registered practitioner and the practitioner is not an employee of the Indian Health Service or a tribal organization) are limited to a 30-day supply of controlled substances via telehealth, after which one of the permitted in-person medical evaluations (with all the required record-keeping requirements) must take place. This will clearly put certain patients at a disadvantage and create a barrier to access for some patients but not for others.

As always, controlled substance prescribing will also have to comply with state laws, which may have stricter requirements than the DEA regulations. Some of the requirements addressed under the proposed rules, such as evaluating prescription drug monitoring program data prior to prescribing, will not be new for practitioners that already meet such requirements under applicable state law.

Nixon Peabody LLP will continue to monitor developments in this area and are available to assist providers and other stakeholders that may require guidance on these DEA regulations and other related end-of-PHE measures.

- Note, this alert focuses only on the DEA proposed rules on telemedicine prescribing of controlled substances when the practitioner and the patient have not had a prior in-person evaluation. The DEA has also issued proposed rules on the expansion of induction of buprenorphine via telemedicine encounter, which are not addressed in this client alert. Due to the similarity between the two proposed rules, DEA is requesting comment on whether it should combine the two into one final rule.

[Back to reference] - See “Telemedicine prescribing of controlled substances when the practitioner and the patient have not had a prior in-person medical evaluation.”

[Back to reference] - Id., page 30.

[Back to reference] - Proposed 21 CFR 1306.05(i).

[Back to reference] - Proposed 21 CFR 1304.04.

[Back to reference] - Proposed 21 CFR 1300.04(o).

[Back to reference]

Appendix

Relationship between prescribing medical practitioner and patient:

Prior in-person medical evaluation by prescribing medical practitioner

- Prescribing a non-controlled medication: Permitted

- Prescribing Schedule III, IV, or V non-narcotic controlled medications: Permitted

- Prescribing buprenorphine as medication for opioid use disorder: Permitted

- Prescribing Schedule II and/or narcotic controlled medications: Permitted

Referral under the proposed rules from medical practitioner who conducted prior in-person medical evaluation

- Prescribing a non-controlled medication: Permitted

- Prescribing Schedule III, IV, or V non-narcotic controlled medications: Permitted

- Prescribing buprenorphine as medication for opioid use disorder: Permitted

- Prescribing Schedule II and/or narcotic controlled medications: Permitted

Telehealth visit without (a) prior in-person medical evaluation by prescribing medical practitioner, or (b) Referral from a medical practitioner who conducted prior in-person medical evaluation

- Prescribing a non-controlled medication: Permitted

- Prescribing Schedule III, IV, or V non-narcotic controlled medications:

- Up to 30-day initial prescription

- In-person visit required for additional prescription

- Prescribing buprenorphine as medication for opioid use disorder:

- Up to 30-day initial prescription

- In-person visit required for additional prescription

- Prescribing Schedule II and/or narcotic controlled medications: Not permitted